|

||||||

|

GAY

FILM REVIEWS BY MICHAEL D. KLEMM

|

||||||

|

Stranger by the Lake Strand

Releasing, Director/Screenplay: Starring; Unrated, 97 minutes |

Paradise Lost

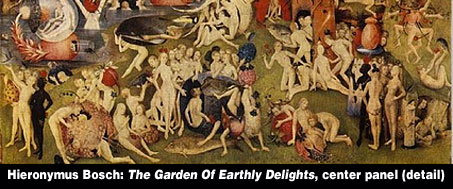

While watching 2013’s Stranger by the Lake, there were times when I was reminded of The Garden Of Earthly Delights, painted by Hieronymus Bosch. The setting for Stranger by the Lake (L’inconnu du Lac), by renowned French director Alain Guiraudie, is a similar idyllic milieu. The entire film takes place at a lake in south France that is a popular gay cruising spot. The beach is dotted with nude men sunbathing and there’s action aplenty in the surrounding woods. Promiscuity is on parade yet much of this is oddly charming. The forest is a carnal Disneyland, yet innocent as a Garden of Eden. However, like the right hand panel of Bosch’s famous triptych, there is also a dark side to paradise. |

|

|

Franck (Pierre Deladonchamps) is a young man, between jobs, who spends his afternoons at the lake. He befriends a pudgy, older man named Henri (Patrick d’Assumçao) who sits apart from all the others, content to watch without sampling the menu. Henri is grateful for Franck’s company each day and watches with sadness, and then with growing alarm, as his young friend becomes obsessed with a dangerous stranger. Franck is drawn to a sexy swimmer whom he watches emerge from the water like a Greek god. His name is Michel (Christophe Paou) and he is handsome, wears a mustache, and looks like a cross between Olympic swimmer Mark Spitz and a gay porn star from the 70s. Franck is smitten and tries to catch up to him when he walks into the woods. Michel has already found somebody else but that doesn’t stop him from smiling seductively from the bushes at the young man who followed him. |

|

|

|

|

A very sexy scene occurs the next day when Michel goes swimming and Franck dives into the water after him. The photography of the two men gliding through the deep blue water is as erotic as it is beautiful. They pass each other and, after Michel turns and flashes that smile again, Franck eagerly follows him back to shore. They strike up a conversation on the beach and are clearly hot for each other. But, alas, we are as disappointed as Franck is when a man, who appears to be a bitchy boyfriend, arrives and Michel leaves with him. Franck hooks up with a bearded man wearing a Batman shirt and later, at dusk when everyone else has gone home, overhears some horseplay in the water. Crouching behind a leafy scrim, Franck is horrified as he watches Michel drown his lover in the lake. But, I said that Franck was smitten with Michel and who cares about a little thing like murder when you’re in love? |

|

|

|

He waits all afternoon on the beach the next day in the hopes of seeing him again. When Michel finally does appear, rising again like a dreamlike apparition from the water, Franck is torn between both desire and fear. He keeps what he witnessed a secret and gives in, without hesitation, to Michel’s advances. Hormones can be a terrible thing and Franck doesn’t seem to care at all that he might be putting his life in danger. (Perhaps he has a death wish; later he fucks him without a condom.) Michel might be a fantasy come true, but it is soon clear that he isn’t boyfriend material. Besides being a murderer, he has no desire to maintain a relationship outside of their trysts at the lake. “I have my life,” Michel tells him, “We can have great sex without eating or sleeping together.” When Franck wants more than that, and also asks too many questions about the man who was drowned, we begin to wonder when Michel will grow annoyed and kill him too. |

|

|

|

Without actually posing the question, the film invites the viewer to ponder why some gay men like to cruise. Why did a man like singer George Michael (who had fame, money and – especially – looks) engage in anonymous sex in lavatories and parks? Is it just a yen for instant gratification with no emotional strings attached? Is the element of danger a part of it too? The film makes no judgments. It is, in some ways, the opposite of William Friedkin’s polarizing 1980 film, Cruising. Whereas Cruising took place mostly in the dark, Stranger By The Lake celebrates the sex in broad daylight and that makes a crucial difference. The cinema is supposed to take us to new places and this film’s method is unforgettable. |

|

|

|

The widescreen cinematography, accompanied by a symphony of nature sounds (with no music), is what makes Stranger By The Lake the hypnotically beautiful film that it is. The lake and the neighboring forest become a self-contained society with its own set of customs. The casual nudity (and there’s a lot of it) evokes Thomas Eakins’ famous painting of young swimmers at a waterhole. I mentioned Bosch’s The Garden Of Earthly Delights earlier because the cruising grounds seem like a mythological setting. The camera pans through the woods and captures explicit sex acts both out in the open and barely visible in the brush. Men wander through the foliage, some watch, some fuck, some politely but firmly reject an unwanted paramour. The men, realistically, are a mix of young and old and many don’t look like swimsuit models. One, in particular, almost looked like a satyr hiding in the bushes. |

|

|

|

Yet somehow these sights in the woods are more charming than salacious. Far from being gratuitous, the sex is necessary in order for the viewer to share Franck’s excitement and understand why he would be so reckless. (We do watch some very explicit sex in this movie - there’s even a close-up of a money shot.) As to be expected, some of this is comic too. Franck runs into a man who asks where the available women are. (“You don’t come here often, do you?” Franck quips.) A nerdy man is often seen watching and masturbating, and he becomes a running gag. When a police inspector shows up later, you initially mistake him for just another voyeur in the forest. It’s fun to watch him get exasperated when no one knows the names of the men they had sex with on the day the drowning occurred. |

|

|

|

Much of Stranger By The Lake is about watching, and it’s hard not to think about Hitchcock. Sir Alfred’s common theme of voyeurism is immediately apparent (the movie is filled with men looking) as is the linking of sex with death. Like James Stewart’s pursuit of Madeline in Vertigo, Franck follows Michel through the woods, obsessed. Viewers may also be reminded of the films of Terrence Mallick where nature takes center stage, in all its scenic and sonic glory, with the characters. The director clearly understands how the sound of blowing wind can be more effective than ominous music. His visual technique is remarkable, utilizing many long camera takes. The film’s pace is languid without ever getting boring. The murder - filmed from a great distance - is an astonishing long take that lasts over four minutes without a cut. |

|

|

|

The film generates a fair amount of suspense during its second half. It is, by no means, a conventional thriller filled with gratuitous shocks but a sense of dread certainly prevails. The lake, at first warm and inviting, now looks vast and dangerous. When Michel suggests going for a swim, Franck’s fear is conveyed by heavy breathing on the soundtrack and the water that extends around him in all directions. Tension and suspicion grows between the two men, especially after each one lies to the police inspector. Franck’s friend, Henri, plays a major part in the climax. He tries to warn Franck that Michel shouldn’t be trusted. “Maybe you’re too gaga to see it,” he says, “but he’s weird.” |

|

Oh, and I almost forgot. Guiraudie won Best Director this year at the Cannes Film Festival for Stranger By The Lake. |

|

|